Does our common sense still exist?

A look at the ways our commonalities and sense of meaning are missing

I don’t know about you, but it feels like the world is particularly messy these days. Over the past few years, I’ve determined that the messiness is a reflection of our inherent paradoxes and a latent inability to manage them. At the top of these paradoxes, the most salient and complex today relates to our need to belong alongside our need to feel individual, unique. After years of declining nativity rates, the influence of the Internet and the evolution of a number of social movements, we’ve become a society that tends to glorify the individual. I’m tempted to say we are suffering from an epidemic of egotism, if not narcissism. While there’s a current that suggests that the world is our village and that we’re all part of the same human race, our links into that broader community are tenuous, if not unrealistic. What is having good common sense if it’s not being realistic. In the process, with a heightened sense of the individual and belonging to an amorphous, enormous and heterogenous global community, we’re less interested in serving our more basic communities. As a result, we’ve lost the feeling of a common belonging and have detached ourselves from a real sense of who we are. This is the commonality and the sense of meaning we are missing today.

There are many problems with this world. If you listen to mainstream media, you’d think there are basically only problems. With media feeding our fear, it’s easy to get bogged down in a negative spiral. Yet, having idealistic hope and good intentions are not the solution. We need to have a more rigorous and candid understanding of who we are and what we want. Without a good understanding of ourselves and awareness of our own inner issues, we’ll be easily swayed and pulled off course.

A lack of commune

It’s in this context that I believe one of the biggest problems of our times is the lack of commune. And this is not a partisan issue. In the West at least, we’ve so privileged individuality that’s padded with a lack of self-awareness that we’ve lost touch with our sense of community. Without community we are doomed. You might read that and say that it’s not true given the trend to globalization, a vigorous focus on Diversity, Inclusion and Equality (“DIE”) and widespread efforts at transculturalism, interculturalism and cross-culturalism. As attractive as the concept may be that we all belong together, we are glossing over a need to stand out. Whether it’s down to a choice of my family over yours, my school over yours, my sports team over yours or my operating system over yours, we inherently have a need to belong to recognizable groups, which some might call tribes. There’s something intuitively right about the Dunbar 150. Whether or not that number is exact, it’s not wrong by any order of magnitude. Our “tribe” or community, where we have a high incentive to remain together and where mutual trust is commensurately high, cannot be much bigger. Obviously, not all tribes are equal, and they certainly aren’t the same. In the wake of this observation, it’s easy to see why we’ve come to politicize identity as a way to make one or other community get more visibility.

Identity politics

While we may think that identity politics is a way of finding a form of community, it’s an artifice, largely built I fear on negative experiences. By politicizing identity, we are giving knives to butcher community. Of course, misogyny, segregation and apartheid policies are intolerable and there have been a number of coinciding forces that have disintegrated our sense of belonging. However, not to allow tribes is equally implausible. The challenge with tribes is that they tend to be exclusionary: I support the NHL Philadelphia Flyers and do not like the Pittsburgh Penguins, even though they’re in the same state in the US. Behind this selection, I’m associating myself with a history, a performance, and some version of a team spirit. It’s the story I tell myself. In this 2021-22 season, despite being 30th out of 32 in the league, I’m holding on to my poor team and that’s part of the deal. With any journey, we have to expect pain and loss. That’s what life is about. As the Greek stoic philosopher Epictetus said, it is not what happens to you, but how you react to what happens that matters. The razor’s edge of tribalism is around discrimination. It’s my belief that by aiming for a total lack of discrimination, as appropriate as such an ambition may be on paper, it’s not natural. We are all imperfect and hold biases. That’s part of what makes us who we are. We’re awfully quick to call out others’ mistakes and errors, but not so hot at seeing them in ourselves. Epictetus recommended in his Discourses about not being angry about faults in others. Specifically, he wrote, “Man, you ought not to be affected contrary to nature by the bad things of another.”*

Managing our paradoxes

In one of our overriding paradoxes, it is in our nature to want to be different and yet have a sense of belonging. At some level, we’ve gone through a pendulum swing where our sense of community (belonging) has been overtaken by a deep sense of individualism and entitlement. This trend has been accentuated, if not marked, by the decline in number of offspring. Whereas 100+ years ago, each of us might have been one of ten children, with one or more dying in infancy, we now are creating families with dwindling number of kids, and with an amorphous if not disintegrating notion of family. Riffing off The Life of Brian by Monty Python, if it used to be that every sperm is sacred, now every individual is sacred. No death is desirable. But today, it’s become uncomfortably unconceivable. When one watches a nature program where a female animal leaves behind a weak or wounded offspring, the reaction is typically: that’s ‘inhumane.’ We feel this out of empathy. But, the reality is that death is essentially natural and inevitable. The great Danish philosopher Kierkegaard wrote that in our dualism, we must reconcile our sense of self and live with our finitude. By obscuring our sense of self, pushing the limits of our freedoms (see “The 1960s Social Movements”), and applying new technologies to avoid aging, we’ve been pushing away further and further the constraints of our body, and whenever possible death as well.

Our relationship with our finitude

In today’s Western world, we’ve lost all desire to countenance death. It’s something that needs to be treated elsewhere, out of mind. Society considers death a topic out of bounds. People fear death and would rather not face it. Old people need to be put in old folks’ homes. The dying need to go silently in hospice. Yet, death is so terribly human. It represents are biggest frailty. Without death, there is no life. As Victor Frankl suggests, without finity, there is no border nor meaning. Nothing is everlasting. We must come to terms with this reality or lose all sense of meaning of our earthly lives.

Life is about challenge

In a similar vein, I see how we have collectively put the individual on a higher pedestal versus our community. Each set of parents considers their singular offspring unique, deserving of the best, saying that little Johnny deserves 110% of our love and affection. Johnny can do no wrong. We must protect our Johnny from all ills. Yet, this form of education is far from helpful to deal with life and the inevitable basket of challenges that are thrown our way. Which gives new meaning to how it is not a good idea to put all your eggs in one basket. But the ruddy truth is that life is about learning to deal with issues, be it health, financial, Mother Nature or other. Let me juxtapose two roads of life, each as a continuum.

Two models

There are two important models that characterize two different philosophies of life, and the clash between them is at the heart our ongoing existential crisis. The first is the model of finitude, where we recognize the difficulties of life, learn from failure, manage pain (mental and physical) and then ultimately face (and embrace) our own death.

The second is the model of infinity where we approach life with hope for a world better, to do good while on this Earth, seeking perfection and tending toward infinity, aka our immortality. This is fundamental to the transhumanist philosophy.

Evidence of this infinity model plays out in how precautionary we are in the face of any danger. For example, as parents, we no longer let children play in the street. We worry about them getting a scrape on the knee or riding on tricycles without a helmet. A big part of my own personal education, so valuable for the rest of my life, was playing full contact rugby, where I learned about my body, suffered injuries and pain, made mistakes and lost games. The improvements made against unnecessary violence and avoidable injuries in the sport are truly positive. However, there’s a need for nuance. We can’t and shouldn’t try to eliminate all failure and pain. Our lives are richer and more substantial if we can reconcile our sense of hope within the borders of our finitude.

The crumbling of community

When I was a child, I remember how my schoolmates and I would discuss together the television program we’d seen the night before. If not physically together, we’d seen the same show in our different sitting rooms, watching the same channel on a similar RCA television. We’d probably be ordered to attend the same church and hear the same sermon. We’d attend family meals, go to the same parties (and later weddings and funerals), and we’d play on the same teams, listen to the same music, and attend the same schools. If choices were limited, community was privileged. Even the media would present unified facts, albeit with different voices and slants. I don’t mean to paint a picture of perfection. Far from it. Dysfunction was rife. But there were many ways that community was maintained. Today, we’re dissociated from one another in so many different ways.

All hail the individual

Today, we’re all encouraged to manifest our differences. Not only is every Johnny better and/or different, but he is also able to identify as he or she or they see fit in the moment. We listen on demand to the shows, films and music we like, when, where and how we wish. Digital tools are personal. From personal computer to iPhone to social media, everything in the commercial world is tending toward hyper-personalization. From Netflix to Amazon to Spotify, we are served with our personal favorites, wishlists and content. As a result, we have no commonality -- much less communality -- left when it comes to our social activities, which used to be the glue of our bonding. As the saying going, we’ve never been more connected, yet disconnected. With the pandemic’s social distancing, we’ve created even stronger barriers and gaps. Working from home – or worse anywhere – we are not just a-social. We’re apatride. We’ve become so individualistic that it’s hardly surprising that we keep hearing about an epidemic of loneliness.

I’m right, they’re wrong

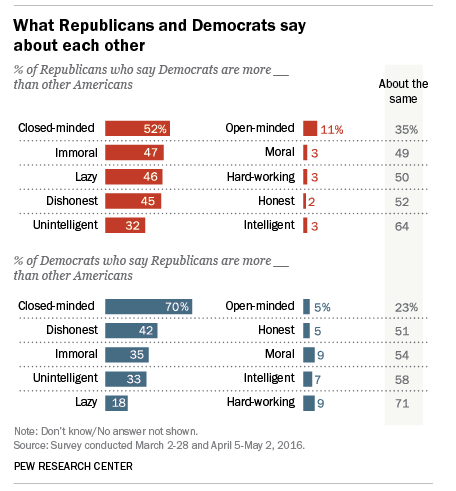

Further, given an ever more antiseptic approach to life – and death – we are no longer willing to countenance difficult debate and/or meaningful differences. Not that all conversations have become absurdly meaningless, but outside of certain close circles, meaningful discussions are rare. According to our grouping, our language is sanitized, and our beliefs are homogenized. Consequently, we’re no longer able to get dirty or move off the party line, nor engage in personal stories without the risk of triggering someone or getting labelled. Certain words and thoughts are considered so offensive that they carry sanctions. On one side of the equation, people prefer to stay quietly among themselves, fuming at the others and perpetuating among themselves their self-fulfilling thoughts. On the other side, in an Instagrammable world, they prefer to show off a hopeful if not perfect picture, rather than engage in difficult discussions or portray a less-than-perfect image. As the 2016 Pew Research showed, both sides think that the other side is so closed minded.

Listen up!

To bridge this gap and open up to one another will require some give and take, a genuine willingness to listen to the other side and to come to the table with a certain humility to accept that the other side could have a point. To her credit, the renowned author Bréné Brown has brought vulnerability front and center. However, we also need to allow for a discussion around developing thicker skins and dealing with pain (both mental and physical). Bringing up children to believe that they’re perfect in a protected world is not to give them any favors for their future development.

Finding a common ground

We’ve created a society where nothing is fixed or even allowed to be fixed. Everything is fluid, including history, facts and science, not to forget gender, age and identity. In university, I felt privileged, if not a bit elite, in studying deconstructionism those forty years ago. [See my earlier piece on Deconstructionism]. With classmates smoking Gitanes and speaking multiple languages, I delighted in discovering alternative meanings to texts, written by well-known authors with volumes of critical analysis. We would strip the words out of their context to provide alternative narratives, especially around figures of speech. We’d regale ourselves on the provocative differences spurred by constraints and nuances of foreign language. But time has come to put ourselves back together again, by reconstructing a common understanding of our history, a better understanding of ourselves and a deeper sense of community. It’s time for us to regain our common sense.

Rising above

In closing, I enjoyed this quote by Henri Astier, a London-based journalist who worked for the BBC from 1991 to 2021 and writes for French and English-language publications. He is referring to the BBC’S attempt to placate and be proportionate for every segment of the population (via Persuasion):

“Ultimately, the way to achieve [BBC CEO] Davie’s goal of remaining “indispensable” to the whole nation is not to try to represent every group and opinion within it. It is to stick with the old-fashioned BBC practice of rising above it all.”

While there’s a current that suggests that the world is our village and that we’re all part of the same human race, our links into that broader community are tenuous, if not unrealistic. What is having good common sense if it’s not being realistic. In the process, with a heightened sense of the individual and belonging to an amorphous, enormous and heterogenous global community, we’re less interested in serving our more basic communities. As a result, we’ve lost the feeling of a common belonging and have detached ourselves from a real sense of who we are. This is the commonality and the sense of meaning we are missing today.

Please let me know your thoughts and reactions. Remember, I want this to be a place of dialogue and meaningful conversation.

Next, we’re going to look at the (good and bad) role of new technologies, including the world online, social media, podcasts chatbots and more.

*The Discourses of Epictetus https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/the_discourses_of_epictetus_with_the_enc/cRHjMJLWk70C?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover, p57

Greetings Dialogos community - my first thought on reading this was to remember (Covey?) the general idea that if you would like to be heard, you must first learn how to listen. My second thought is (I work in Washington, DC) how to rise above - and find this missing commonality in this harshly divided political landscape. My third thought is acknowledging that you have really nailed it with the concept of the lack of commune, or huge growth of this lack. Final thought, THANKS for creating at least one space where we can at least agree to talk about these things!

Great points. The question of common sense requires some common perspectives. In many ways we are more connected virtually than ever but disconnected from a common experience. A lot to think about here.