Have you found (y)our path?

In a world of so much senselessness, here are some thoughts and strategies for putting more meaningfulness into what we do and say.

I don’t know about you, but I when I’m walking in the street, I love to imagine how a stranger’s personality might be etched into their facial expression. Does the furrowed brow mean a worrier? Does a downward facing mouth mean a grumpy person? These are what we might call first impressions. They may or may not be true, but they certainly have an impact on your thoughts and actions. I might see ‘my’ truth in their face. At times, it may even be true. The harder work is to look in the mirror and know who you are looking at. If there is a crisis of meaning, as described by best-selling author Jamie Wheal (guest on my podcast here), there’s an accompanying misunderstanding of who we are and what makes something genuinely important. When we lose touch with who we are, we are prone to grab onto whatever we can, that helps to enliven us. In the process, we are subject to personal and increasingly volatile feelings that get triggered by fears. Let’s not pander to these. I suggest that, as a society and on an individual level, we’d be better if we all gained perspective on what’s really important. To find true meaning in my own life, I’ve discovered a vein of work and a passion that drives me, even when the news around us is dour. It’s helped me navigate the craziness and to distinguish the forest from the trees.

Why so much need for meaning?

Some people – especially the media – like to talk about and hype up that there are different epidemics and crises proliferating around the world. It’s hard to know what’s fact or fiction, particularly in the face of so much fact-free reporting. Here is a sprinkling of headlines about the different broad-based crises that have been published in the last year by generally well-known publishers:

Democracy: The Global Crisis of Democracy—And How to Reverse It (Stanford University - Feb 2022)

Cost of Living: Inflation hits fresh 40-year high of 9.1% amid cost of living crisis (Sky News – Jun 2022)

Loneliness: How loneliness is damaging our health (NYTimes - Apr 2022)

Depression: Why experts are calling Depression a Global Health Crisis (Healthline - Feb 2022)

Masculinity: I guess we have to talk about the ‘masculinity crisis’ in America again (Fast Company - Nov 2021)

Disease: Monkeypox can create Covid-like crisis, if… (Mint - Jul 2022)

Drugs: Opioid addiction crisis in the United States… (UCLA – May 2022)

Racism: Oakland California declares racism a public health crisis (NPR – Jun 2022), a headline that got its start out of Harvard University: Racism is a public health crisis, in the midst of the COVID pandemic, and was reported here in the WaPo (Sep 2020)

Unemployment: Lockdowns and the US Unemployment Crisis (National Library of Medicine – Oct 2021). Funnily enough, there’s also the issue of full employment reported by the US Chamber of Commerce (Jan 2022)

Immigration: The long history of the US immigration crisis (Foreign Affairs – Mar 2022)

…you name it. In sum, there seems to be a crisis about almost everything being reported somewhere…

In addition, of course, there are the perennial -- if not chronic -- topics of geopolitical tension, social injustice, climate change, cyber insecurity, poverty, human rights, terrorism and wars. The point is that, given the seriousness of the topics, just talking about these crises can give people a sense of meaning. The prevailing thought goes like this: I think about a heavy topic, therefore I exist … because I gain gravitas. People naturally feel enlivened by their emotions. The unifying concept is fear. In light of a plethoric choice of abjectly frightful subjects, it inexorably leads many people having an existential crisis. Maybe we are now experiencing a crisis of crises? As Viktor Frankl wrote many decades ago, the lack of meaningfulness may be responsible for three burgeoning societal ills: aggression, addiction and depression (aka the ‘mass neurotic triad’), all of which seem to be worthy headlines for today’s media. While we might be excited by the potential of new technologies and the dynamic and innovative times we’re living in, it’s hard not to pay attention to the naysayers and doomsday predictions, with the media fanning the flames and playing on our fears.

The emptiness inside

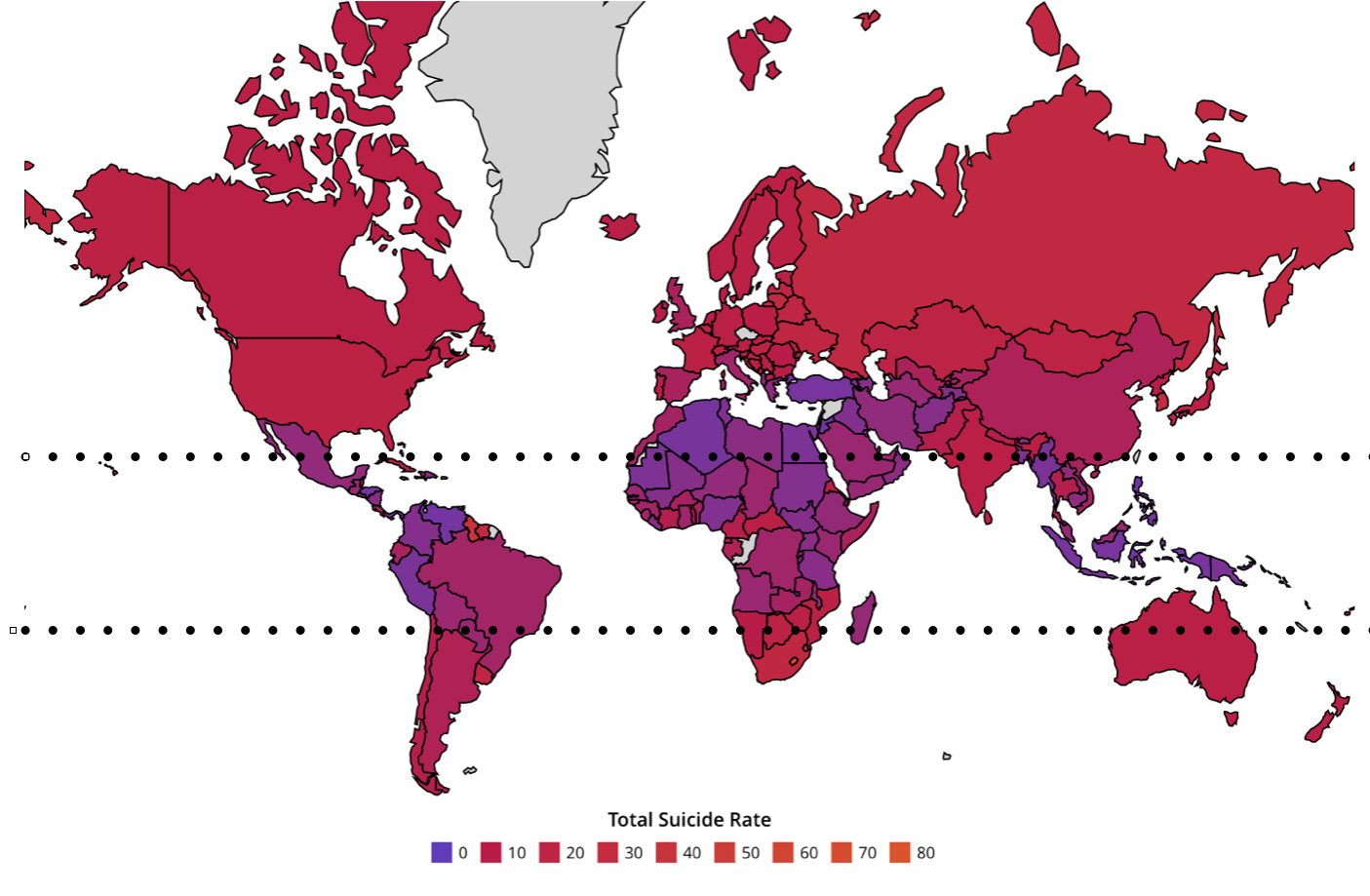

It’s possible that one of the reasons for this situation is that people (in the developed world, anyway) are looking at these crises as a way to fill the void inside. I would not be the first to suggest that we are suffering from a crisis of meaning. [See this NIH research]. In a world of increasing senselessness, we seek to find ways to inject meaning. But the problem with engaging with these global issues is that (a) they’re pretty darn depressing, and (b) the solution is out of our little hands. I think of the many furrowed brows who, most earnestly, are wringing their hands and fretting over the pain, horror and/or dismal prospects. For all the reported ‘progress,’ it seems we’re not better off. As reported by many different studies, the level of unhappiness and dissatisfaction in society – and at work – has not improved despite higher levels of GDP, convenience and comfort. Oishi and Diener’s study, Residents of Poor Nations Have a Greater Sense of Meaning in Life Than Residents of Wealthy Nations [PDF], published in 2014, explores the relationship between wealth, a sense of meaningfulness and suicide. The graph below in figure 1, taken from the Oishi/Diener report, shows how poorer countries like Sierra Leone, Togo, Laos, Kosovo and Senegal, can have a higher sense of meaning in life, while countries on the far right (i.e. in terms of higher GDP per capita) can suffer from a lower sense of meaning in life, such as in Hong Kong, Japan, Spain, France and Belgium…

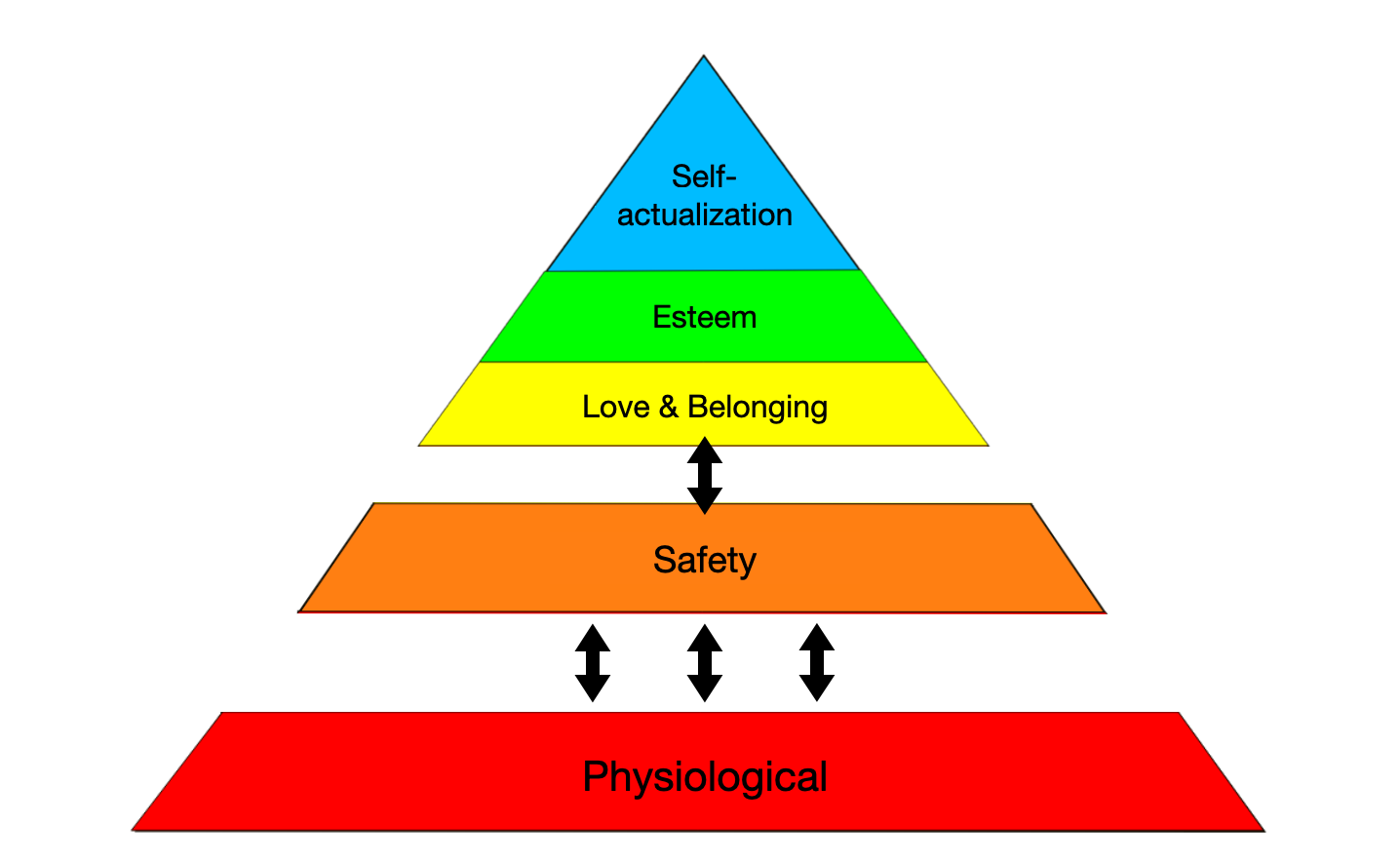

The study exposes how suicide rates were often high in the richer countries, like South Korea (4th in terms of suicides per 100,000, from the WHO in 2019), Belgium (17th), the US (23rd), Japan (25th) and Sweden (28th). As the map shows below in figure 2, there’s a purple belt (low suicide rates) running through Latin America, Africa and Southeast Asia. One might be tempted to think it’s about climate and/or lesser changes in length of days, since these countries are broadly lined up between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn.

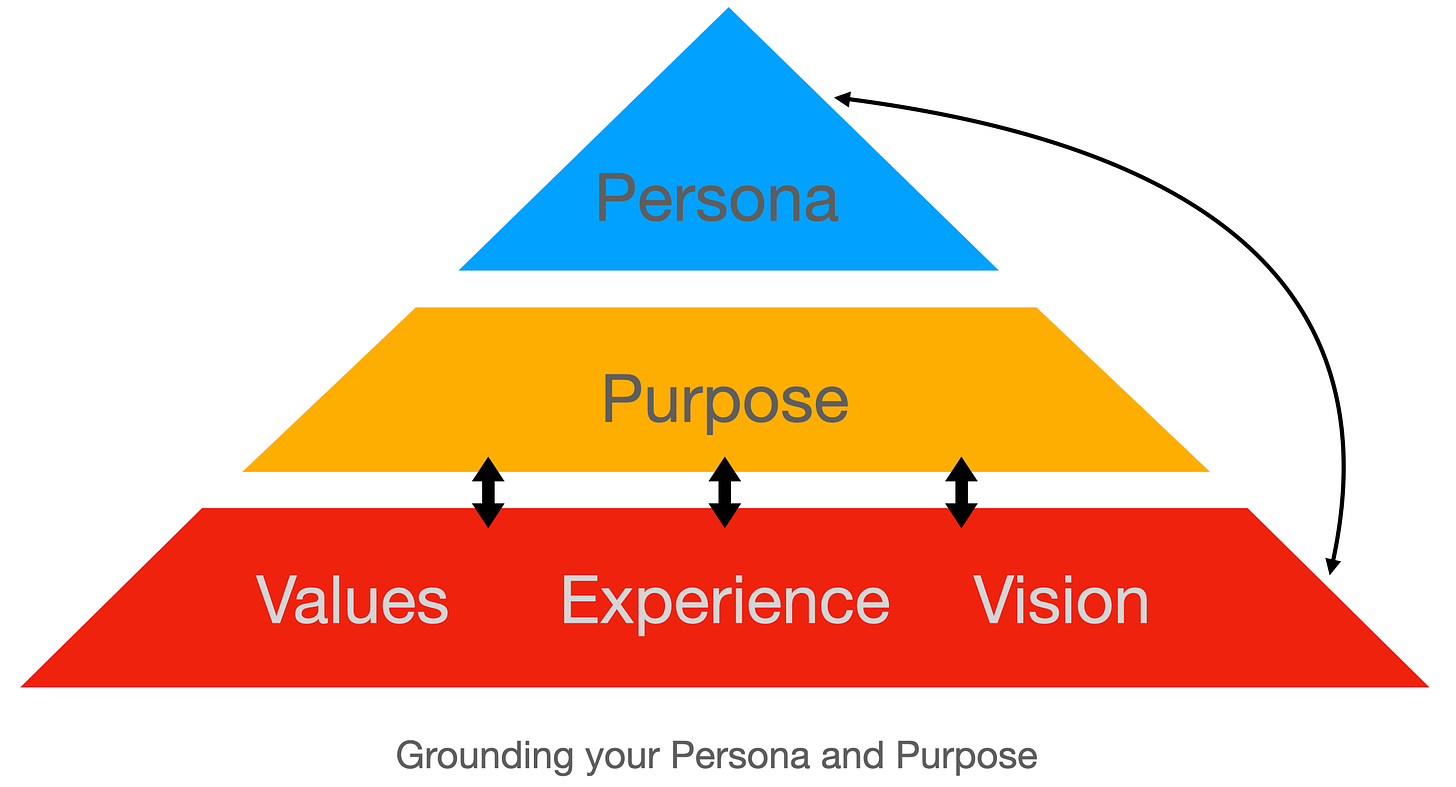

Of course, the reporting of suicides may or may not be accurate in these lesser developed countries. Nor do we have clarity as to the reasons. A low rate certainly doesn’t indicate in itself a greater level of happiness or fulfilment. Yet, the higher levels of suicide in developed countries would seem to be indicative of greater existential issues. Insofar as, in the name of ‘progress’, we worry less about the basics (food, shelter, physical safety…), it seems we have ended up worrying about other ‘higher,’ less resolvable problems. As we go up Maslow’s famous pyramid (see figure 3), the needs are less life-threatening, yet seem somehow to become more precarious. My belief is that we need to forge a greater connection back into our basic needs in order to put perspective on our problems and remind us of our base reality.

The more our perspective and sense of purpose are detached from our own deepest reality, the more insecure we become.

On the back of increased individualism, it seems that the pandemic brought a hyper focus on the notion of safety. As Haidt and Lukianoff discuss in their bestselling book, The Coddling of the American Mind, there are two components to safety: physical and mental. Surely, we are much safer physically; but, especially true in the US, it seems we have swung toward a society of hyper prevention-ism and lawsuit-at-the-ready precaution-ism. As part of a move to safetyism, so-termed by Haidt and Lukianoff, we now seek emotional safety, protected from words, images and concepts that could potentially trigger a negative reaction, in some cases regardless of intention or context. The expression of stepping on fragile eggshells seems at times sadly appropriate. When you speak to people who live in troubled countries such as the Ukraine, Afghanistan or Syria, they have an entirely different sense of priorities and a different style of need for safety. With the swirling changes in the air, with worrying pronouncements about being closer to nuclear war than at any other time since the end of the Cold War, I think we are in need of more meaningful and robust conversation around some of these sensitive subjects.

The meaning of meaning?

In our quest to find more meaningfulness in our lives that appear fragile because of the prevailing emptiness, it will make sense to dig in on what is the meaning of meaning. How meaningful is anything to anybody? The book, The Meaning of Meaning: A Study of the Influence of Language upon Thought and of the Science of Symbolism, by Ogden and Richards, although published a century ago, remains a good epistemological starting point for purposes of establishing meaning, whether through words or symbols. But, beyond the crude meaning of things, we all have a different understanding of what is meaningful. Depending on one’s past experiences, expectations and context, a star in the sky or a cute kitten photo can fill someone with different feelings. There’s an interesting challenge in trying to define meaningfulness since it’s different for everyone. Moreover, the sense of meaningfulness is filled with both emotional and rational elements, the former of which is by essence personal and subjective. To the extent something is meaningful, it is my contention that it must be converted into words in order to have lasting power. Just as the integration process in psychedelic-assisted therapy is where the rubber hits the road, meaningfulness of an event, activity or symbol requires an explanation.

Symbols, signs… and meaning

Have you ever seen something and, without great reflection, felt the need to whip out the phone and take a photo? It’s almost instinctive. It could be a fleeting thing of beauty, someone who looks famous passing by, or an incident that appears as if it could be noteworthy. I know that I’ve done this plenty of times. More often than not, I attach a vague sense of importance to the image. And then it just sits there, collecting digital dust, in the Photos app. The question is: what do these signs and symbols really mean? If you’ve never come across the term of apophenia, then you’ll likely be surprised to learn that there’s a word for attributing meaning to unconnected events. According to Merriam-Webster, it’s “the tendency to perceive a connection or meaningful pattern between unrelated or random things (such as objects or ideas).” Not everything is meaningful, not even at an individual level. We might feel or see things and connections, but it’s possibly more a reflection of a lack of meaningfulness elsewhere. In an upcoming article, we’ll look at the layers of meaningfulness and how we can find deeper meaning in our activities and conversations. In a powerful interview I conducted on my French podcast with the world-renowned negotiator, Laurent Combalbert, he insisted that a sense of meaning should not be disassociated from one’s genuine understanding of the world, i.e. our mission on Earth, our vision of the future and our core values. But how many of us do that hard work?

Finding purpose

Today, many people have made saving the planet their purpose. And, as deeply concerning and commendable as that cause is, it doesn’t resolve the fundamental issue of a deeper self-knowledge. As Carl Jung wrote on individuation, whereby one gets rid of the false masks and the pretentious persona or image one projects of oneself, our need is to gain a truer understanding of ourselves. When a sense of purpose is disembodied from the real self (whether we hide from it or don’t know it properly), it becomes volatile. The consequence is that we attach an ever-greater importance to this cause/purpose because we feel it re-presents us. To the extent we naturally form our persona in function of our relationship with the environment, the desire to protect our Earth is, with pun intended, only natural. To diminish or aggress my purpose is to defy me, or at least the image of me that I am trying to project. I posit that this disassociation is why we see so many people suffering from mental health issues today in the developed western world. At its core, it’s an existential problem.

Pattern recognition

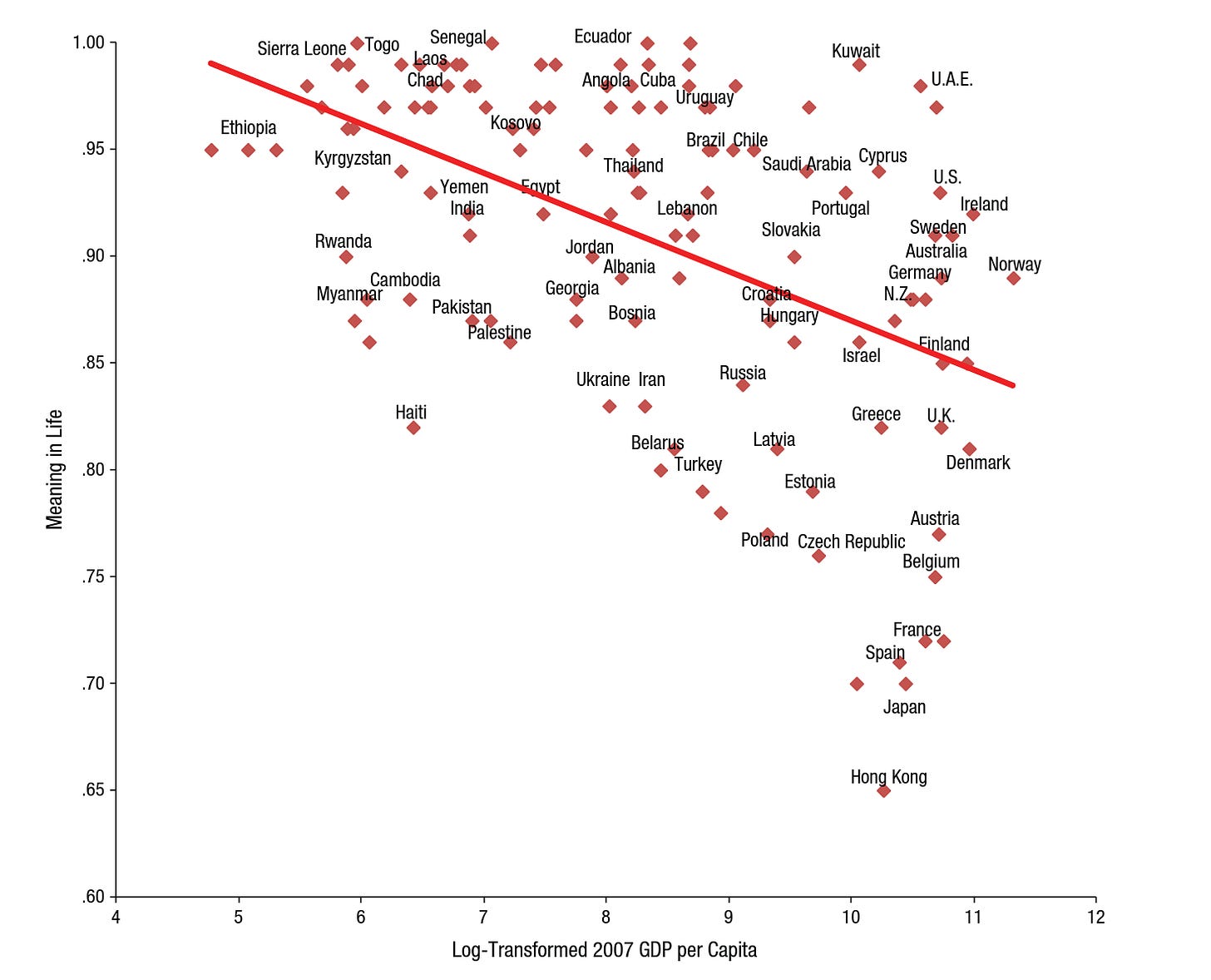

As I lean into the potency of gaining a clearer and stronger sense of self, I’m also keen to encourage pattern recognition. There’s no clear writing on the wall, much as our encrusted beliefs might have us think. We need to open our eyes to patterns but ground our perspective in analysis and critical thought. It becomes important to avoid apophenic visions, such that disparate and meaningless dots don’t all of a sudden take on undue weight. I think of seeing shapes and meaning in clouds, the inkblot Rorschach tests or even psychedelic hallucinations. What counts in all cases is the link into the self. If you see a sheep in a cloud, that doesn’t mean sheep are more or less important. It doesn’t mean you have to be a sheep (or become a black sheep as my friend, Brant Menswar, author of The Power of Black Sheep values, might say). Per the integration that follows psychedelic-assisted therapy, it’s about connecting that stimulus into who you truly are. One must have congruence between the persona and our underlying values, experience and vision (see figure 4).

Linking in with myself

To be consistent, thus, I should reiterate (as I’ve done before), why I am passionate about this Dialogos. My personal purpose – which has become a guiding principle of my life – is to elegantly elevate the debate. It comes from a past of having seen so much domestic hostility, whether that was on the home front (messy divorces), caustic relationships or fights among seeming friends and family. I’d see so many arguments break out where none seemed necessary if both sides had sought more data points (aka non judgmental questioning and listening). I’m someone who prefers to avoid confrontation. As a result, my daughter says I can have a dismissive attitude. [She’s right]. No wonder I struggled with the corporate environment at L’Oréal where the meeting room was literally called a “Salle de Confrontation.” I enjoy debate, jousting, and playing the devil’s advocate, but I don’t like it when people raise their voices or use offensive language to make a point. It provokes a visceral reaction. Any point can and should be made in a civil manner. In any event, that’s my mojo.

Lack of faith + narcissism = ?

If today’s world is suffering from so much division and divisiveness, I believe one of the key reasons has been a decrease in faith. It’s also because we are hell bent on glorifying the individual, hence I’d argue the increasing focus on narcissism, as argued by San Diego State psychologist, Jean Twenge, who contends that there's evidence to show that we're living in a culture of escalating narcissism. Looking at Google Trends in figure 5 below, and comparing against another trendy word, empathy, it seems that searches for narcissism are off the scales. Heightened narcissism and a lack of faith is a potent cocktail.

A return to what is common

In the US alone, in a survey conducted in 2021, the number of people identifying as agnostic, atheist or ‘nothing in particular’ has risen to 29% from 18% in the last ten years [PEW Research]. This lack of faith means a lack of a unifying belief. In Douglas Murray’s book, The War on the West, he quotes his friend, the economist Deepak Lal, “Everybody claims that after the age of Christianity, we are going to enter an age of atheism, whereas it is perfectly clear that we are entering an age of polytheism. Everybody has their own gods now.” We may prefer to believe we have the ‘right’ and freedom to believe in our individual form of spirituality, but the key word here is individual. As I wrote in an earlier post on Dialogos, we have lost our common sense, running after a hyper individualization. Ironically, this has led to a greater sense of loss and despair because everything is dynamic and volatile. We are neither grounded by a common bond with our community, nor by a greater understanding of our true selves. This is the fundamental problem which has befallen much of western society. Instead, we are creating missions and flying diverse flags with greater and greater unicity – in other words disparity – in an effort to underscore our existence, the ultimate goal of which is to make the individual stand out and live for longer, if not forever (Model of Infinity). Whether through greater spirituality (including religion) or a better understanding of ourselves, we all need to connect into and integrate the things that really tie us all together, our common truth and our deepest humanity: we are all imperfect and are destined to live finite existences. It’s not about believing more in the Model of Infinity (hope and goodness) or in the Model of Finitude. It’s about reconciling the two and living with both of them.

Self-responsibility will be critical

In a world where it’s often easier just to cave in to the “system” and to follow mainstream narratives, I am calling for a higher degree of self-responsibility. To use Nietzsche’s terms, otherwise we may wish to feel resentment (be the victim) because of our station in life. Through ressentiment (in French, which literally means re-feeling), he wrote that we seek to hide or anaesthetize our pain through emotion. In our quest for a better society, we must start with ourselves and take ownership of our own path and our own responsibility to make ourselves better. And I have resolved that I must be on the front line, modeling this behavior myself. If we let loose our resentment against the system – or whatever other vessel, group or ideology there is to blame – we will lose touch with ourselves and make the divisions more rancorous. Devoid of rationality, a grounded morality and genuine self-responsibility, we will drive ourselves into oblivion.

Find (y)our path

To finish a positive note, I know that the work I’ve done on myself to find my own North Star has been so helpful. For starters, it focused my activities on others. It gave me a sense of purpose in my corporate career and entrepreneurial ventures. It made my work more meaningful. It has powered me through bad news, drops in energy and ambient morosity. And for the upcoming turbulence, it will provide a compass by which to guide me.

It’s about finding your path in our world.

If you’d like to exchange with me on how to find a sense of purpose that is congruent with yourself and your place of work, please drop me a line!

The harder work is to look in the mirror and know who you are looking at. If there is a crisis of meaning, as described by best-selling author Jamie Wheal (guest on my podcast here), there’s an accompanying misunderstanding of who we are and what makes something genuinely important. When we lose touch with who we are, we are prone to grab onto whatever we can, that helps to enliven us. In the process, we are subject to personal and increasingly volatile feelings that get triggered by fears. Let’s not pander to these.

Further reading:

Man’s Search for Meaning – Viktor Frankl

The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations – Christopher Lasch

The Meaning of Meaning – Charles K Ogden and Ivor A Richards

The Power of Meaning: The true route to happiness – Emily Esfahani Smith

The Power of Black Sheep Value – Brant Menswar